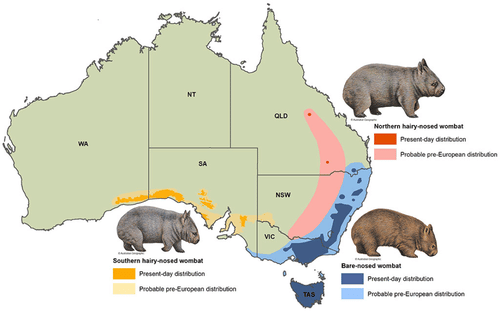

Currently, there are three extant species of Wombat:

- The ‘Northern hairy-nosed Wombat’ (Lasiorhinus krefftii) listed as ‘Critically Endangered’

- The ‘Southern hairy-nosed Wombat’ (Lasiorhinus latifrons) listed as ‘Near Threatened’

- The ‘Common Wombat’ (Vombatus Ursinus) listed at ‘Least Concern’.

The ‘Common Wombat’, was first documented by colonial settler, George Shaw in 1800.

The perception this title creates, is that the ‘Common Wombat’ is just that… common – plentiful, abundant, living a full and heathy wild life. Unfortunately, after more than two centuries of human impact and persecution, climate catastrophes, introduced disease and predators, this is far from the truth. As a result, Wildlife Conservationists, Academics, Researchers, NGO’s, NFP Organisations, Charities, Rescuers, Carers and Advocates are instead beginning to refer to the ‘Common’ Wombat as the ‘Bare-nosed Wombat’. With the intention to put pressure on government and taxonomic officials to officially change their title.

This incredible and unique native species, found nowhere else on earth, is said to have diverged from other species approximately 40 million years ago. The Wombats closest living relative is the Koala, who is now sadly listed as ‘Endangered’ due to similar reasons experienced by most native species. Perhaps if the Wombat had as much local and international attention as its Koala cousin, it too would be recognised as a Threatened Species.

Whilst Wombats face the same, and in fact, additional key threats (such as legal and illegal culling/killing) they are still listed as being of ‘Least Concern’ under the Federal Government’s ‘Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999’ (EPBC) and therefore not considered a Threatened Species.

This is primarily due to the fact that to change this listing, it requires scientific data including a population census, which due to the remote underground locations of Wombats and their nocturnal nature, is extremely difficult to obtain.

Without Federal Government recognition of the species being listed as Threatened, and with the challenges Wombats have experienced and continue to face, there is no federal funding provided for the research and data collection required by the Threatened Species commission in order to list the species as such. So, it remains an ongoing battle for wildlife advocates, to try and help raise awareness, save and protect the species as best they can.

Key threats which have and continue to cause significant decline in the ‘Bare-nosed’ Wombat population include:

- Habitat loss through land clearing for urban development

- Human persecution through legal and illegal culling/shooting, trapping, poisoning and burrow destruction

- Road incidents – road deaths increase year on year with the ever-increasing urban sprawl into wildlife habitat – more roads, more people, more cars, faster cars and higher speed limits.

- Slow reproductive system – Wombats have only one baby (joey) approximately every 2 years, who on average has a 50% chance of survival to adulthood

- Predation by introduced feral and invasive species such as foxes, dogs and cats;as well as domesticated dog attacks.

- Sarcoptic mange – a highly contagious, invasive introduced parasitic mite (Sarcoptes scabiei) that burrows deep into the Wombats epidermis, rapidly multiplying and causing intense pain and itching. As the infestation progresses Wombats suffer a multitude of excruciating symptoms (as well as deafness and blindness) for many months and as a result, ultimately die. Mange can be treated (with a high level of difficulty), if affected Wombats are found before the infestation has progressed beyond a certain point. Sarcoptic mange is a critical welfare crisis which most state and the federal government continue to ignore.

Wildlife rescuers and carers are volunteers who dedicate their time and money into caring for and raising sick, injured and orphaned Wombats, as well as treating Wombats in the wild who are affected by mange (whereby medication needs to be applied topically every week, for 15 weeks, to every Wombat in the colony). They are seeing first hand, the significant demise and decline of the ‘Bare-nosed Wombat’.

Just like our homes, Wombat burrows can take years of hard work to construct and establish. They can be up to 30m in length and feature sleeping ‘chambers’ for comfort and safety. This unique, ancient marsupial has a hard plate in its behind which is uses to crush a predator against the roof of its burrow when threatened. They famously have cube-shaped poo and a backward facing pouch for their joey, so it is protected whilst Mum is digging.

Burrow destruction, by climate disasters such as floods, or by human intervention (deliberate destruction, filling in or preventing the Wombat access ie via a one-way gate) can be just as cruel as outright killing a Wombat, as it leaves them homeless and highly exposed to so many dangers. Can you imagine losing your home and having nowhere to go?

If a Wombat happens to survive this predicament, they need to try and find an alternative location for a possible new home, during which time they are highly susceptible to so many dangers including predation, dog attacks, road strike, attacks by other wombats (as they are highly territorial and can critically harm each other), sleep deprivation, disorientation, starvation, stress, disease, illness and death.

Australia has a long, sad and tumultuous relationship with the Bare-nosed Wombat.

In the 1880’s European settlers declared Wombats as a ‘noxious’ species and introduced a 5 shilling reward for each animal killed. The main reason being that Wombat burrows provided safe havens for rabbits – an invasive species introduced by the settlers themselves. Due to the impact of rabbits, farmers were legally obliged to control them, lest they be fined, resulting in the destruction of Wombats and their burrows in an attempt to control rabbits. This bounty led to the death of thousands of Wombats and by 1897 Wombats in the Riverina area were considered extinct. In 1906 Wombats were classified as ‘vermin’ and in 1925 another a bounty was introduced. This saw the removal of a substantial amount of habitat and greatly reduced numbers and range of the Wombat. Many places in Australia have been named after the Wombat, including a large number of places where they are now locally extinct in the wild, such as Wombat State Forest in the Central Highlands of Victoria and Wombat Hill in Daylesford.

Unfortunately, this persecution has continued ever since colonisation and still continues today. For example, in Victoria alone, the State Government issued 252 wildlife control licenses to private landholders, which allowed for the lethal removal of 3,374 Bare-nosed Wombats in just one year (DELWP 2019). The Licenses are provided in response to the negative impacts Wombats are perceived to be causing on a property. The Department states that licenses to kill native animals are issued only as a last-resort once all non-lethal and non-invasive methods have been attempted. However, there is no physical investigation or monitoring of such at the site by the Government – it is merely all just paperwork.

Once widespread throughout southern Australia, the Bare-nosed Wombat’s habitat is now restricted to limited pockets of the south-eastern states as well as Tasmania. Most of these areas have undergone significant bushfires and more recently, several serious flood events. And yet, even whilst all Australian native wildlife is ‘protected’ by law (under both State and Federal legislation), and, even without any population data, the State Governments continue to issue permits to landholders to lethally “control” thousands of Wombats each year. And the Federal Government simply turn a blind eye.

We can all help by learning more about the plight of all Wombats, the challenges they face and how to peacefully co-exist with these iconic creatures. Become familiar with your local wildlife carers and see how you can offer support. Help by raising community awareness, fundraising and writing to your local councillors and petitioning state governments to cease issuing permits to kill, and to provide funding for carers and the treatment of mange; volunteer to participate in mange treatment programs in your area, or perhaps become a Wildlife rescuer or carer. Wildlife rescuers and carers undergo specialised training and carers are required to be registered and licenced to keep Wombats.

As Australians, who share this land with such incredible ancient native species, it is our responsibility to do more to protect Wombats.. imagine losing such an iconic Australian during our lifetime.. one that has been here for over 40 million years! They deserve so much more respect and understanding.

Treeswift Wildlife & Nature would like to thank Megan Healy of Wild Things of Oz for generously contributing this article for World Wombat Day – 22nd October 2022

1 thought on “The ‘Common Wombat’…what’s in a name?”

Wombats are so misunderstood. They are very loving animals, especially when in care. And they are our natural bulldozers of the earth, aerating the soil as they turn it over. Beautiful post, Megan.